Introduction

From September 2014, Financial Education became part of the secondary school curriculum in England.

A culmination of years of campaigning, the change was greeted as a great advance. For some, particularly in the policymaking world, there was a sense of “job done!” – now it was on the curriculum, secondary school students would have good financial education.

When the change was announced, The Money Charity were pleased to see financial education finally recognised as something all young people should have access to. But we were sceptical that it would impact what actually went on in schools. In itself, unless matched by a large input of resources and incentives for schools, it would be unlikely to change much in the classroom.

Two years on, what has happened?

Having been one of the main organisations delivering financial education in schools, both before and after 2014, we at The Money Charity saw very little uptick in demand from schools. And, anecdotally, teachers rarely mentioned the curriculum requirement. Meanwhile, long standing complaints about insufficient time, resources and leadership support continued.

And this Spring, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Financial Education for Young People reported the continuing need for “strengthening school provision” – highlighting that much work was still to be done, and championing a redoubled effort. We gave our input to this report, but felt that the anecdotes we drew on needed to be more robustly evidenced.

This report is our answer to that. Based on a survey of 126 teachers and in depth interviews with a further six* , it is our attempt to answer the question of what happened. In it, we explore the extent and quality of financial education in England, ask what the barriers are to schools improving what they offer, and discuss how schools and policymakers can improve the situation.

We find that, while most schools deliver some finance education, teachers have little faith in its quality and are held back by insufficient time, negligible resources and school leaderships who do not view it as a high priority. Teachers we surveyed called for greater resources, and clearer leadership, and a mixed model of provision that includes direct delivery by experts from outside schools.

A snapshot of Financial Education

Financial education is happening, but not as well as it should

The one piece of good news is that nine out of ten schools we surveyed are delivering some kind of financial education. On the face of it, a success. But scratch beneath the surface and the picture of financial education does not look so rosy.

Teachers are not confident in the quality of financial education.

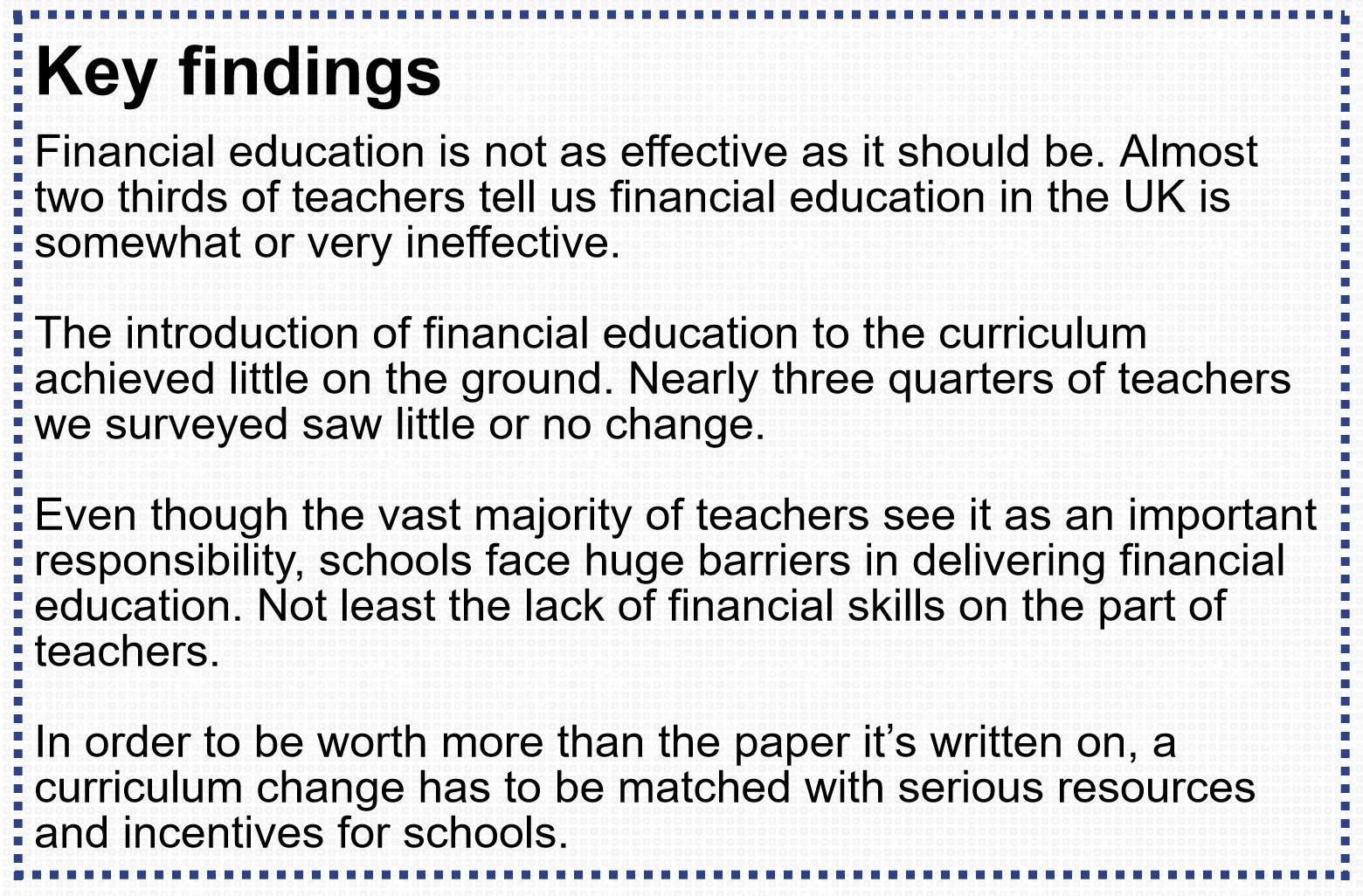

And while most schools we surveyed are delivering it, teachers are still very pessimistic about how good financial education is in England, with just under two thirds describing it as either somewhat or very ineffective, and none calling financial education very effective.

And to put perspective on these figures, while we sent the survey to a comprehensive list of schools around the country (see PDF), those who responded were self-selecting and will have been more interested and engaged in financial education than most.

and will have been more interested and engaged in financial education than most.

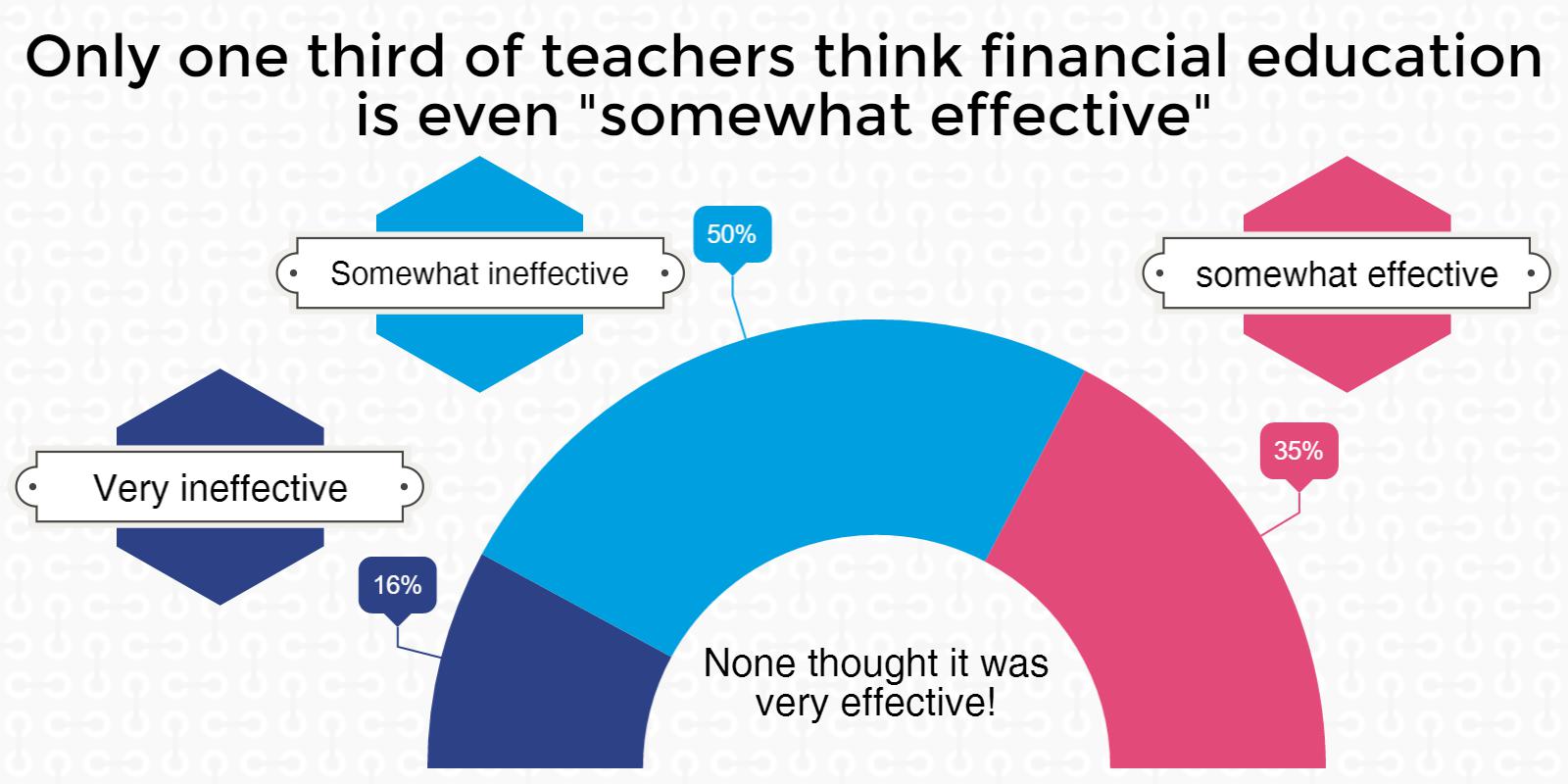

As a consequence, it is safe to assume that the results we have paint a rosier picture of financial education than actually exists. For instance, a national poll of teachers conducted for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Financial Education (APPG) found that just four in ten teachers nationally were aware of the 2014 curriculum change, compared to two-thirds of those we surveyed.

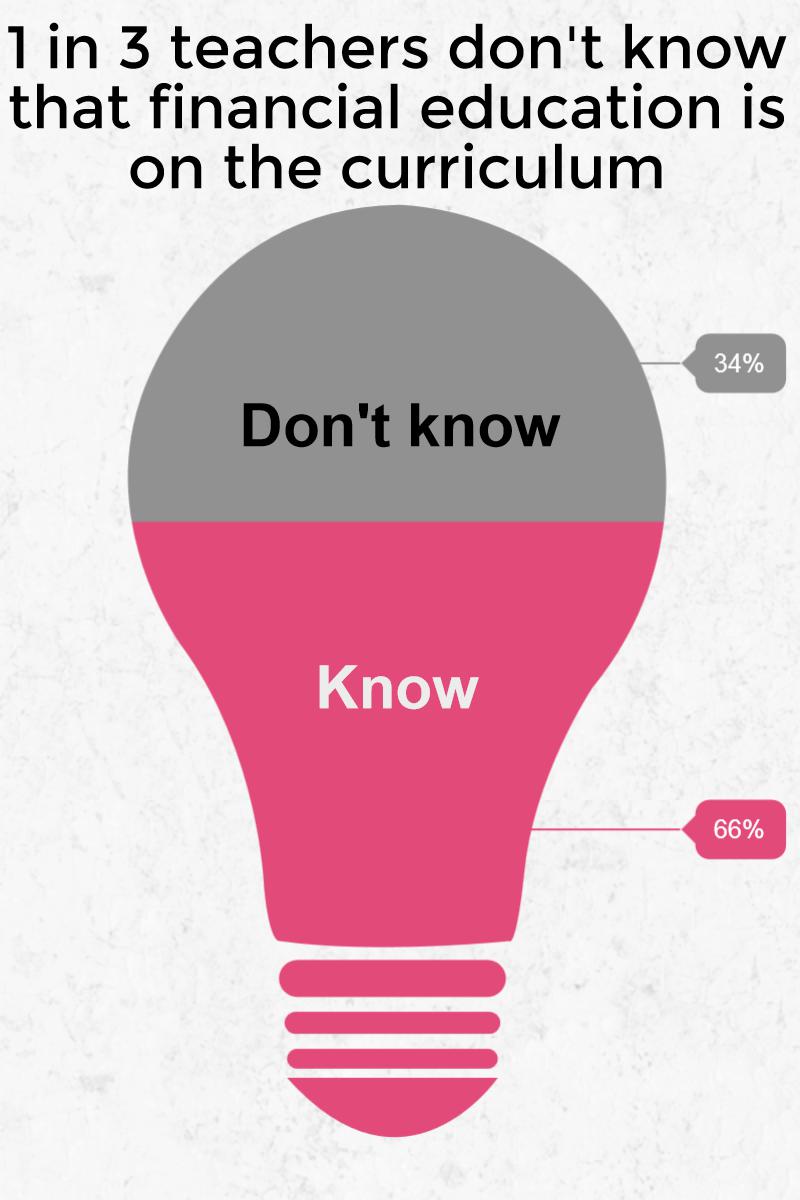

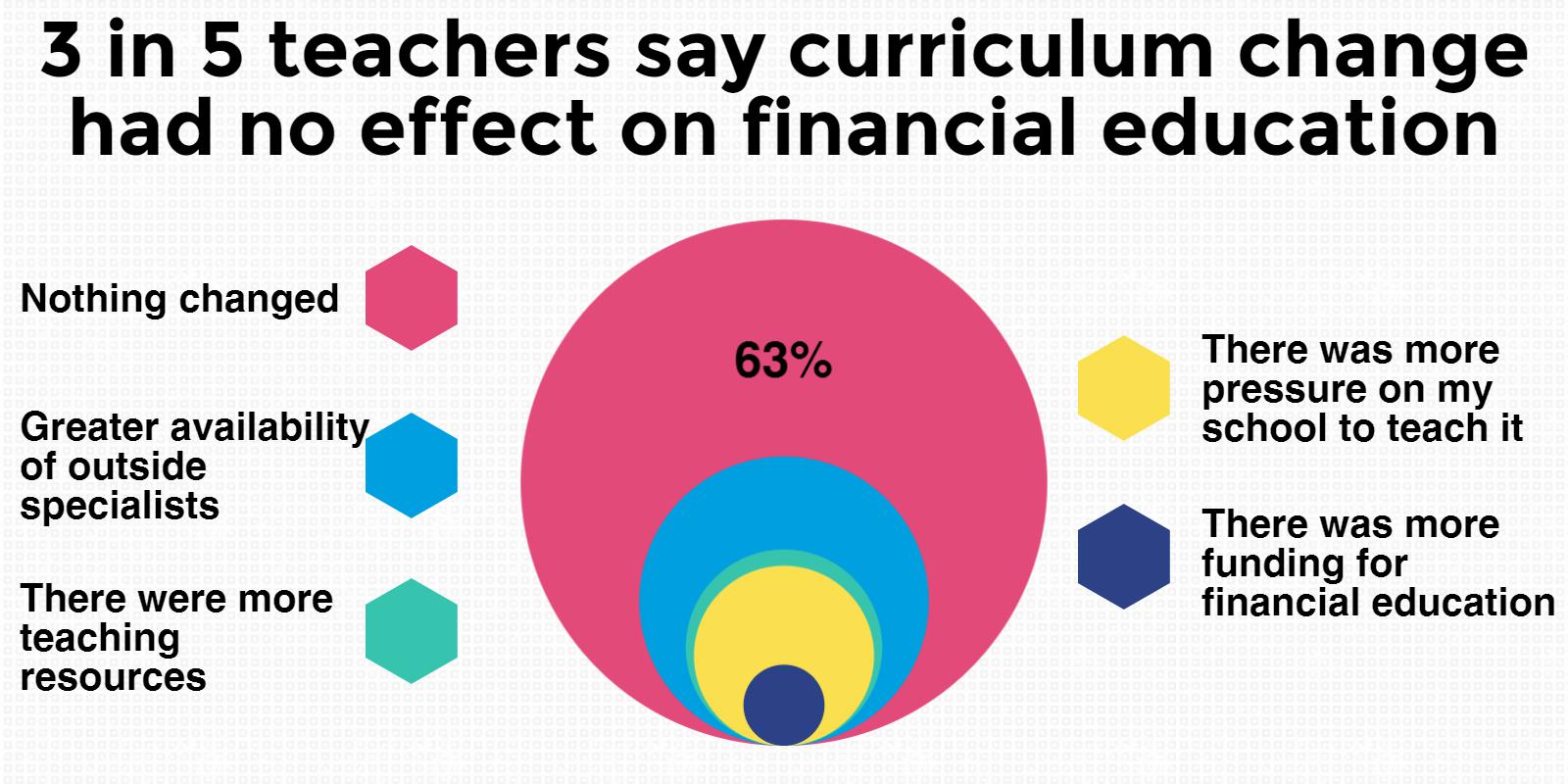

Even with this likely bias, more than 70% of schools said the statutory obligation made no or very little impact on the teaching of financial education. And a full third of teachers do not even know that the change took place!

First, for most teachers, no clear effect was visible when financial education became a statutory obligation. The availability of outside experts to deliver classes in schools did increase for some schools, but other resources, funding or the pressure felt by schools barely shifted.

Given that little changed two years ago, teachers were simply expected to deliver financial education by themselves, if at all. But as our research shows, the vast majority of teachers believe that their schools do not currently have the expertise to do this.

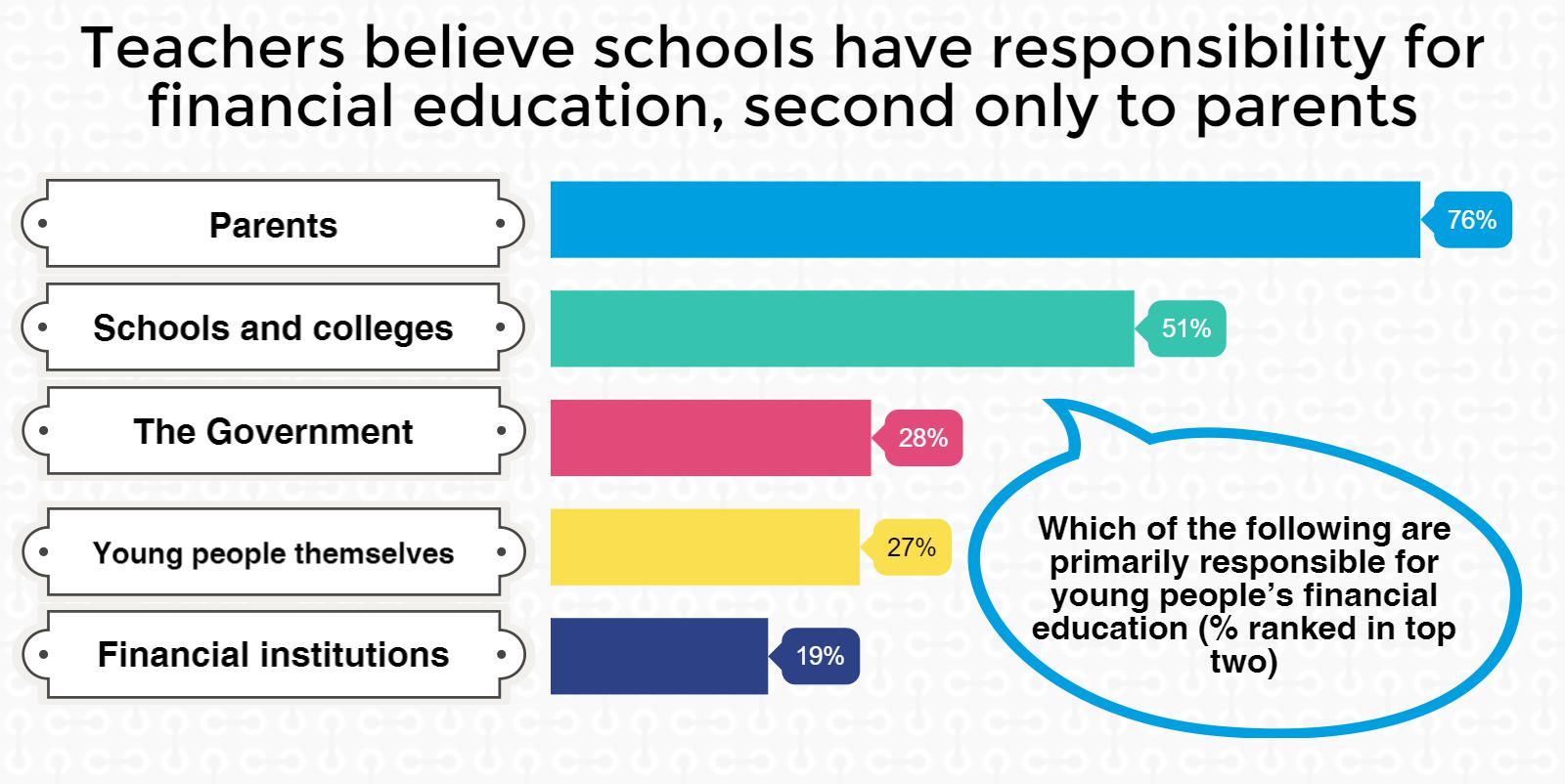

There is also no shortage of willing from teachers to focus on financial education, nor a feeling that it is not the responsibility of schools. After parents, teachers believe that schools have the second greatest responsibility for delivering financial education.

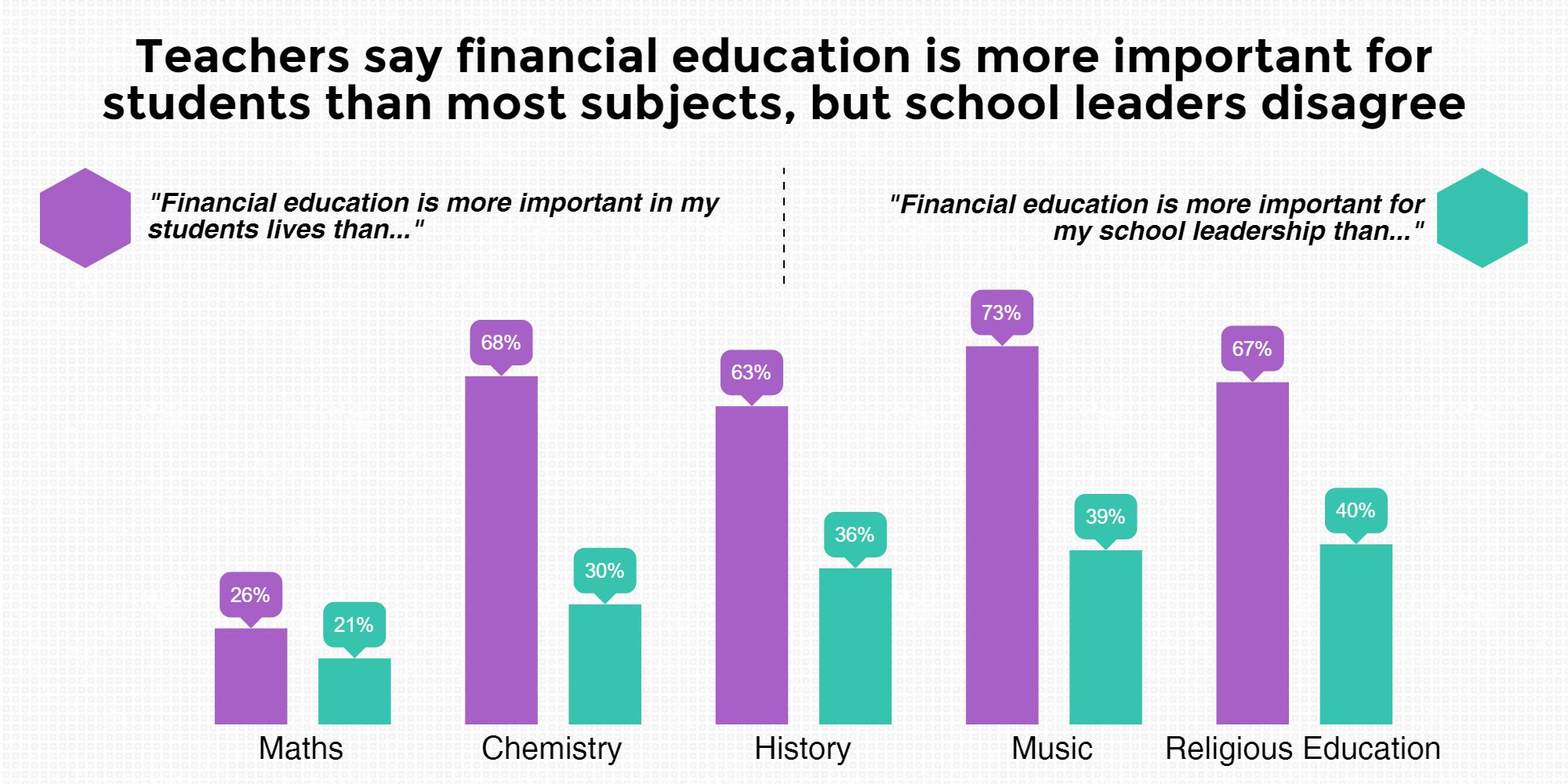

Teachers also believe that financial education is vital, with nearly two-thirds telling us that it is more important in their students’ lives than Chemistry, History, Music or Religious Education.

The picture drawn by our research is of individuals and schools trying earnestly to deliver financial education, with most schools offering something. But that is not enough to ensure it is of good quality. So, if teachers believe schools have the responsibility for providing financial education, and that only subjects like maths are more important for young people’s lives, what stands in the way of schools delivering good financial education?

drawn by our research is of individuals and schools trying earnestly to deliver financial education, with most schools offering something. But that is not enough to ensure it is of good quality. So, if teachers believe schools have the responsibility for providing financial education, and that only subjects like maths are more important for young people’s lives, what stands in the way of schools delivering good financial education?

Barriers to schools

Our survey finds that despite willingness from schools and a formal requirement for Local Authority schools to deliver financial education, significant barriers stand in the way of teachers and leaders making this a reality.

Barrier 1: low prioritisation of financial education

One big answer lies in the incentives that schools face, and the priorities that leaders have.

In stark contrast to what teachers believe is important for young people, they feel very different priorities coming from their school leaderships. All those subjects that teachers believe are less important than financial education, are perceived to be more important to school leaderships.

Financial education is not seen as more important than Maths, either for students’ lives or for school leaderships. But for all the other subjects we asked teachers about. There is a significant mismatch between what would help young people and what school leasers push for.

For instance, 68% claimed that financial education was more important for students than chemistry, but only 30% said their leaders saw things the same way.

This phenomenon exists because very little external pr

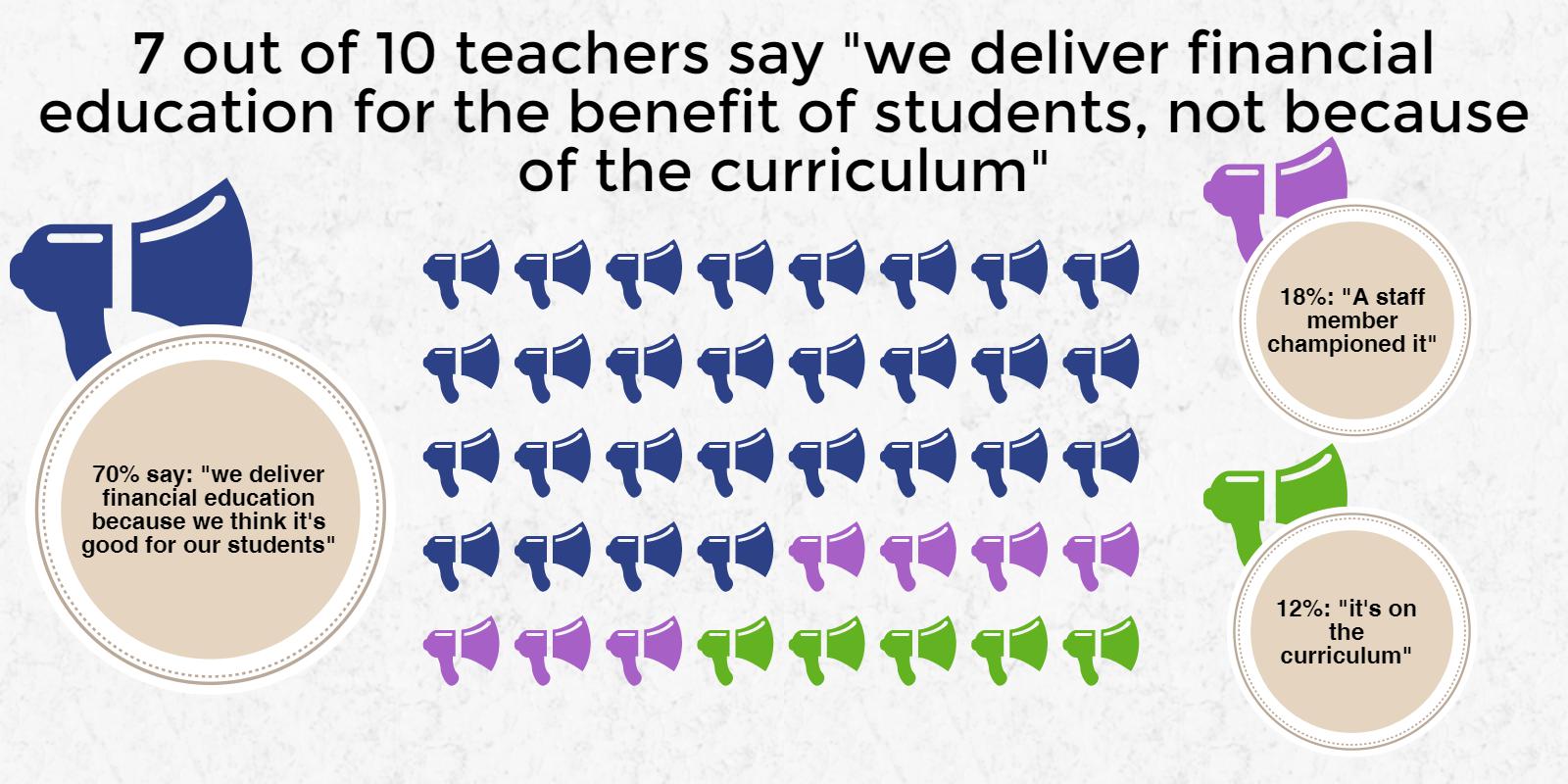

This phenomenon exists because very little external pr essure is felt by schools to deliver financial education. Where schools are providing it, it is almost always driven by the perceived need of young people, or because of a passionate staff member, rather than statutory obligations or parental wishes.

essure is felt by schools to deliver financial education. Where schools are providing it, it is almost always driven by the perceived need of young people, or because of a passionate staff member, rather than statutory obligations or parental wishes.

The problem with this is that it requires independent action within schools, for a member of staff to recognise  that financial skills are valuable for students and then to have the power within the school structure to champion its delivery and argue for the required resources in time and funding. When financial education, led by an individual, does get off the ground in schools it runs the risk of becoming dependent on that teacher, who may later move on or get promoted – leaving the subject they spearheaded adrift.

that financial skills are valuable for students and then to have the power within the school structure to champion its delivery and argue for the required resources in time and funding. When financial education, led by an individual, does get off the ground in schools it runs the risk of becoming dependent on that teacher, who may later move on or get promoted – leaving the subject they spearheaded adrift.

Barrier 2: A lack of clear leadership

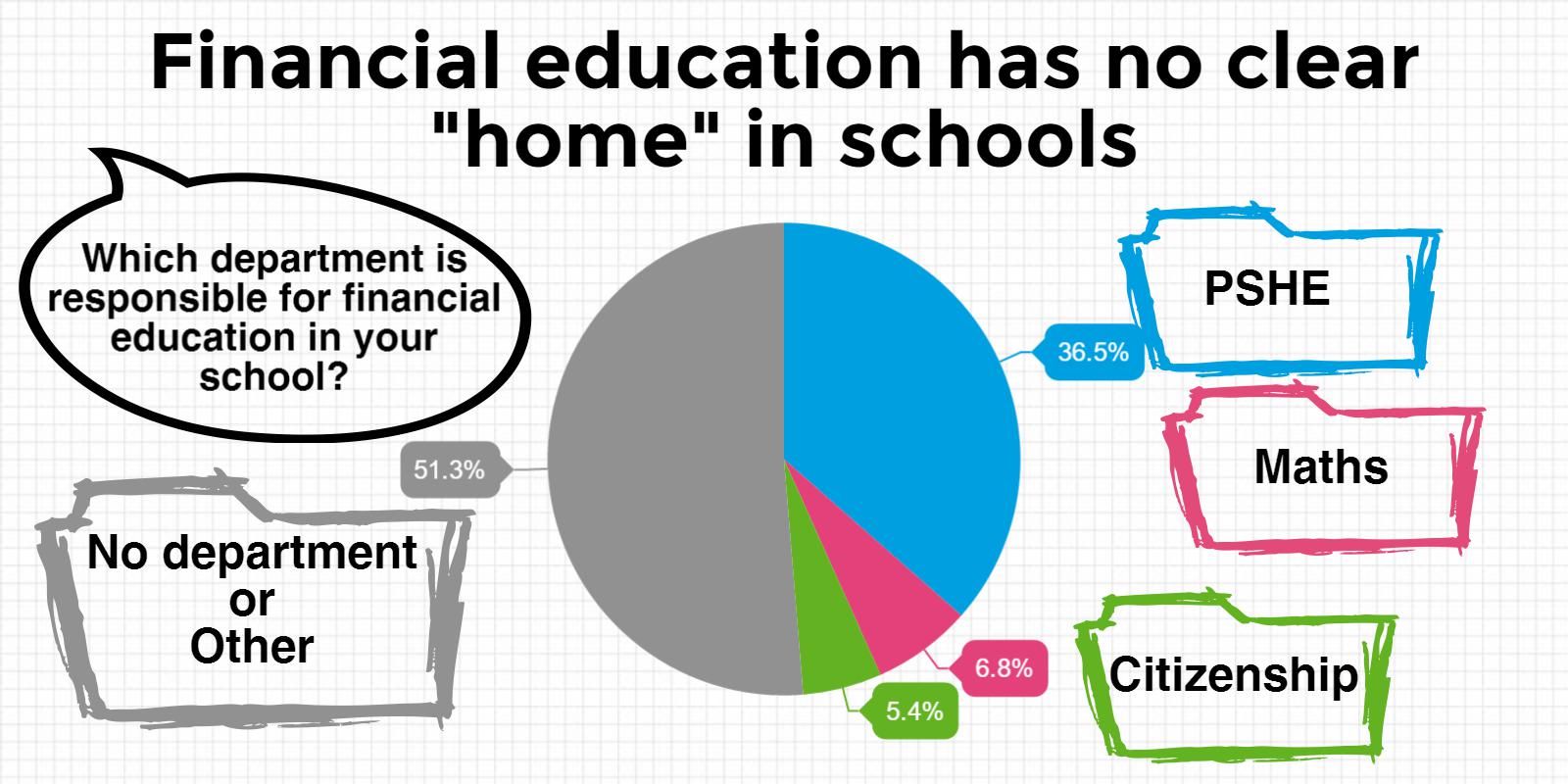

On top of this, while subjects like drama, biology or history are led by named members of staff, for three in five of the schools we surveyed, it is not even clear where the leadership for financial education is supposed to come from – the ownership is split between many departments, or held by none.

The consequence of this is that nearly 60% of teachers feel that financial education is not well led in their schools, and well over 90% feel that it’s not well led overall.

Barrier 3: Pressure from exams and Ofsted to focus on other subjects

In the interviews we carried out with teachers, the elephant in the room during any  conversation about teaching something that is not already a core subject is the exam results and the OFSTED ratings. Anything new in a schools’ offering has to compete with the pressure to keep up the grades or meet Ofsted’s inspection framework.

conversation about teaching something that is not already a core subject is the exam results and the OFSTED ratings. Anything new in a schools’ offering has to compete with the pressure to keep up the grades or meet Ofsted’s inspection framework.

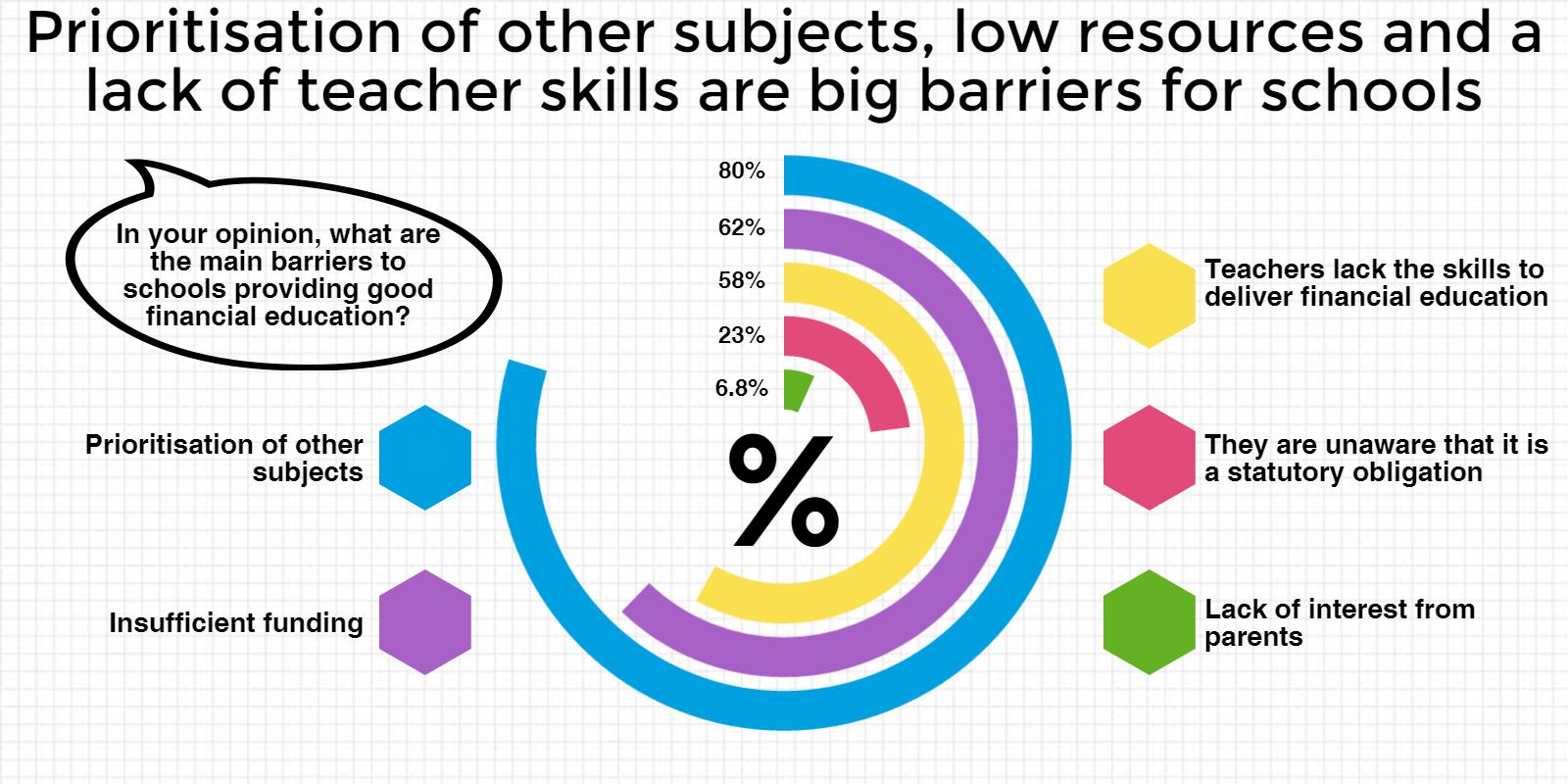

Time, resources, and the attention of the school leadership gets poured into teaching things that sit within examined subjects. Financial education does not, and 80% of teachers cite the prioritisation of other subjects as one of the main barriers to delivering it.

Time, resources, and the attention of the school leadership gets poured into teaching things that sit within examined subjects. Financial education does not, and 80% of teachers cite the prioritisation of other subjects as one of the main barriers to delivering it.

Barrier 4: Teachers don’t have the skills they need

Teachers are people, just like the rest of us. Having the skills and qualifications to teach English or History, or even Maths, does not mean that you are a financial expert. To expect teachers of PSHE or citizenship to be a ble to deliver financial education is unfeasible without training or direct delivery from outside experts (explored below).

ble to deliver financial education is unfeasible without training or direct delivery from outside experts (explored below).

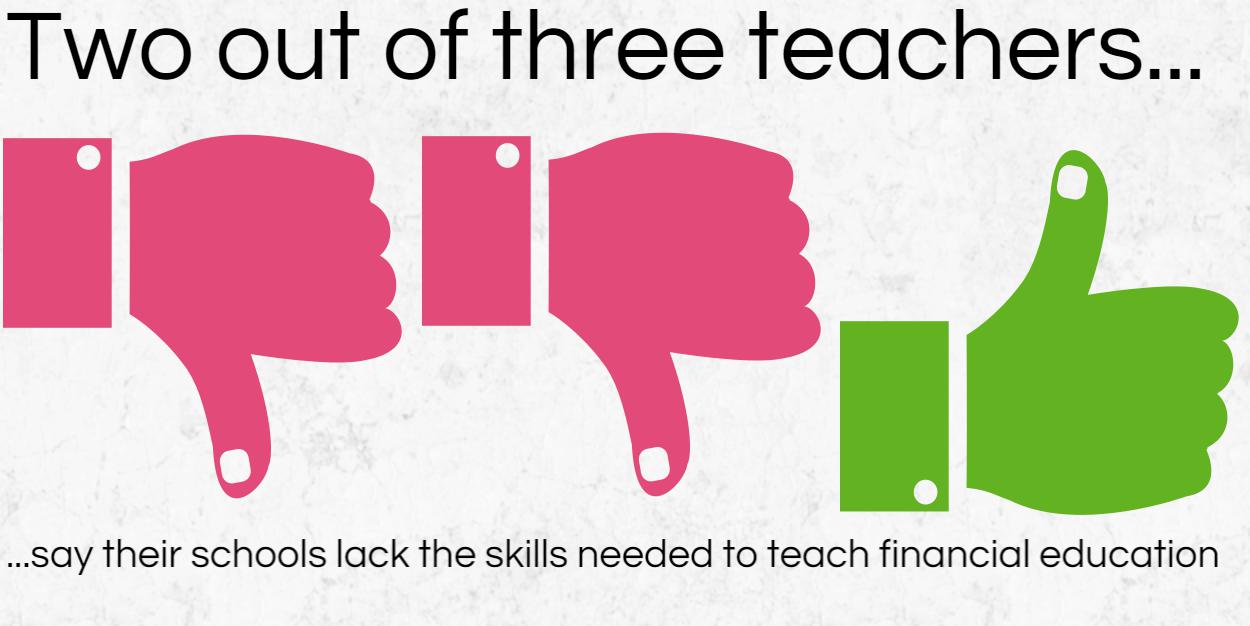

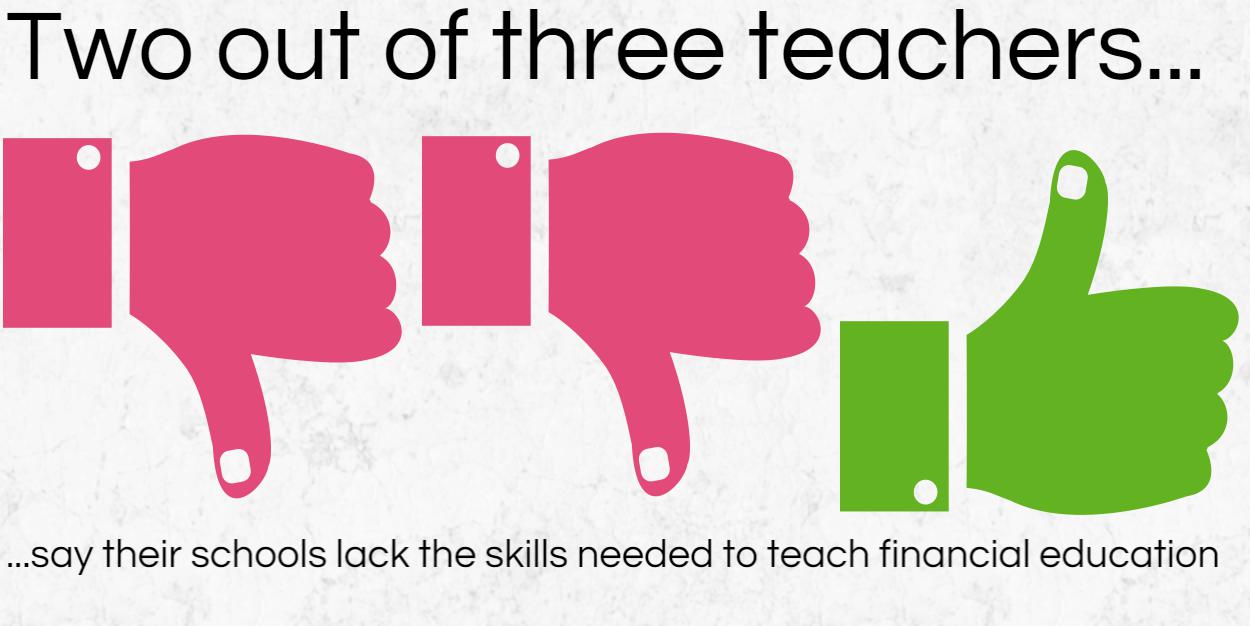

Two years on from the curriculum change, only just over a third of teachers believed colleagues in their school had the skills required.

This lack of financial skills in schools’ existing staff is much of the reason why schools are so open to direct delivery by outside experts such as those provided by The Money Charity. 80% of teachers believe that outside help is needed to help deliver financial education and nearly nine out of ten think that students learn better from speakers with specialist knowledge than from members of permanent staff. However, this direct delivery schools are asking for is undermined by the lack of resources given to financial education…

This lack of financial skills in schools’ existing staff is much of the reason why schools are so open to direct delivery by outside experts such as those provided by The Money Charity. 80% of teachers believe that outside help is needed to help deliver financial education and nearly nine out of ten think that students learn better from speakers with specialist knowledge than from members of permanent staff. However, this direct delivery schools are asking for is undermined by the lack of resources given to financial education…

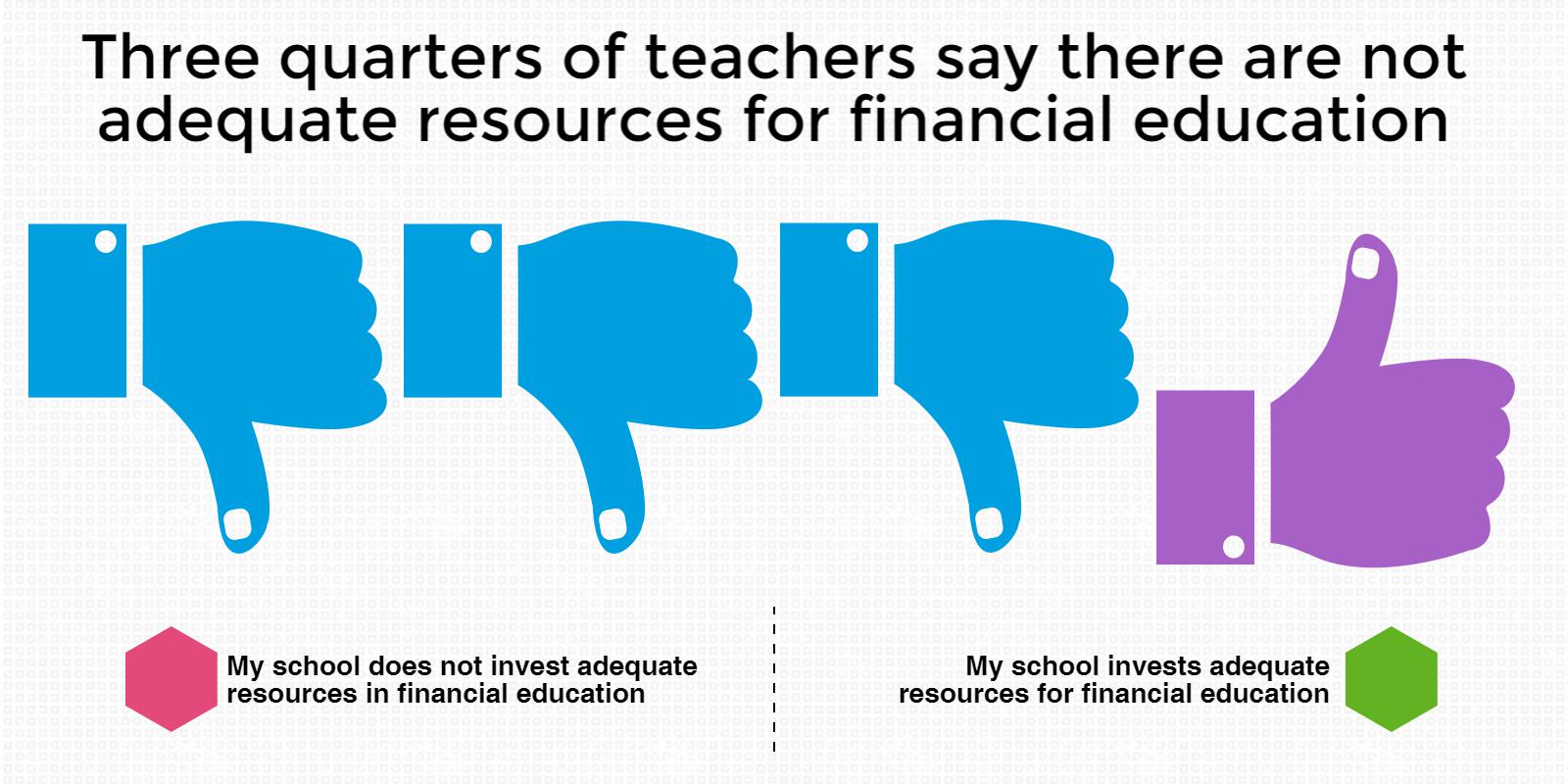

Barrier 5: Inadequate resources

Because financial education is not properly prioritised and led, it is no surprise that three-quarters of teachers feel that financial education does not receive the funding it needs i n their schools.

n their schools.

Without adequate resourcing, the lack of financial skills that teachers have, and the little time afforded to them to deliver financial education cannot be bridged, either through training or bringing in experts.

These five barriers reinforce one another and leave financial education in the position of being a secondary, discretionary offer for schools, the first item for the scrap pile and last to the table.

These five barriers reinforce one another and leave financial education in the position of being a secondary, discretionary offer for schools, the first item for the scrap pile and last to the table.

What can we do?

If putting financial education on the curriculum was not enough to ensure that it is delivered at a high quality in schools across the country, what could?

The first thing that policymakers should understand is that if they want change, they have to take it seriously. No one-off action like putting financial education on the curriculum can transform the situation without being accompanied by resources and incentives for schools. Teachers and school leaders do respond to the needs of their students and the requirements set by central government, but only if the right carrots and sticks are put in place.

What do teachers say?

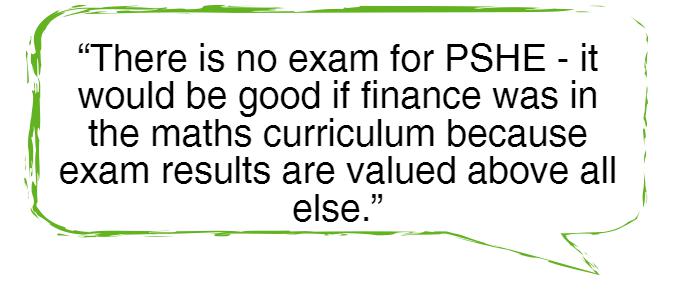

Teachers are pretty clear on this. Making financial education part of an examined subject would do more to push it up school leaderships’ agenda than anything else.

This speaks to a truth well understood by the teachers we interviewed, who consistently spoke about the pressure from school leadership to direct time and resources to examined subjects.

This speaks to a truth well understood by the teachers we interviewed, who consistently spoke about the pressure from school leadership to direct time and resources to examined subjects.

A new ‘managing money’ component to Maths

The Maths curriculum in England already contains the provision to:

“Solve problems involving percentage change, including: percentage increase, decrease and original value problems and simple interest in financial mathematics.”

But although this provision exists, the Maths problems in exams and in classrooms are often mechanistic and divorced from real-world application. Teaching a young person to calculate rates of compound interest without talking in a holistic way about financial lives does not amount to real financial education. Simply because a mathematics question has a pound sign attached does not mean that financial education is being delivered.

Instead, we echo the call made in the APPG report on financial education for a:

‘Specific ‘managing money’ strand to the programme of study for secondary level Mathematics to ensure it is taught in the context of real-life scenarios. Ofsted should also give a clear steer that this ‘real-world’ approach is what is expected of schools.’

Strengthened role for PSHE

But not all financial education can be taught in Maths, or is particularly mathematical in nature. To understand how finances work is emotional, social and literate as much as it is mathematical. So w hile context needs to be given to teaching of financial education in Maths, Personal, Social and Health (PSHE) is a far more appropriate home much of financial education.

hile context needs to be given to teaching of financial education in Maths, Personal, Social and Health (PSHE) is a far more appropriate home much of financial education.

However, the status of PSHE in schools is low. Without being examined, and with teachers having to include a vast array of completely unrelated subject material, often within very limited timetabling.

often within very limited timetabling.

In order to for financial education in PSHE to be given the time and priority it needs, it has to be examined, or at least written into Ofsted’s Common Inspection Framework so that schools know it will be a key part of what they are inspected for. Without these changes, there will always be “something better” for school leaders to expend their energies on.

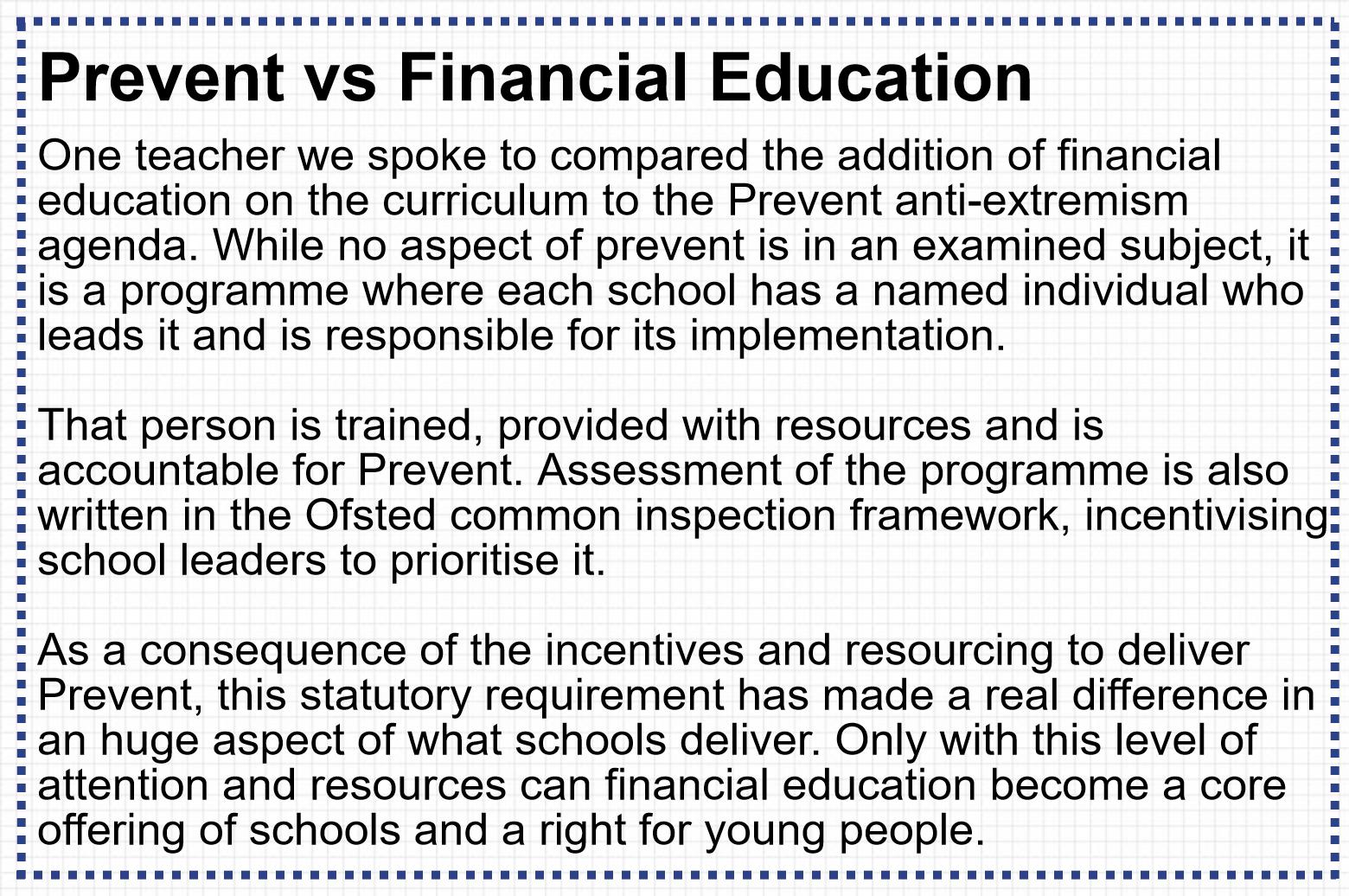

In our short comparative case study, we compare financial education to the delivery of the Prevent anti-extremism agenda, another new obligation for scho

In our short comparative case study, we compare financial education to the delivery of the Prevent anti-extremism agenda, another new obligation for scho ols to deliver. The contrast could not be clearer. While the delivery of both the prevent programme and financial education are technically obligations for schools, one is given leadership resources and is inspected, while the other exists only on paper.

ols to deliver. The contrast could not be clearer. While the delivery of both the prevent programme and financial education are technically obligations for schools, one is given leadership resources and is inspected, while the other exists only on paper.

Direct delivery as part of the mix

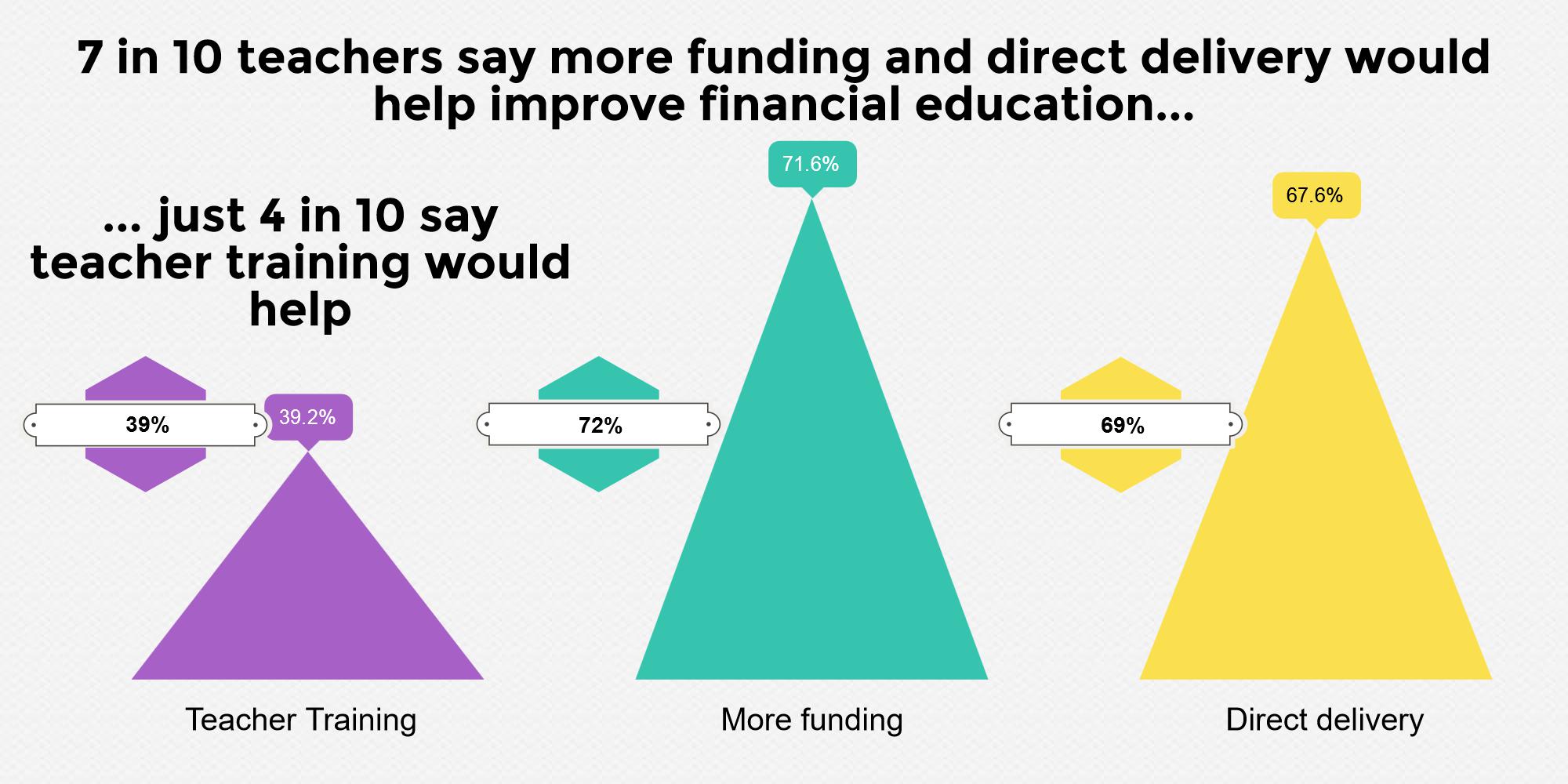

If policymakers and school leaders wish to improve the delivery of financial education, teachers call for greater practical help: more resources like lesson plans and the funding for direct delivery of financial education by outside experts.

Even if schools can overcome the barriers to offering financial education outlined above, finding the leadership, and space in the timetable they need, they’re still left with the challenge of how be

Even if schools can overcome the barriers to offering financial education outlined above, finding the leadership, and space in the timetable they need, they’re still left with the challenge of how be st to deliver it.

st to deliver it.

The first thing we know is that simply asking teachers to put it into their tutorials or PSHE classes is not enough. Nearly seven out of ten teachers don’t believe that their schools are equipped with the skills required to teach financial education. More than 80% believe that teachers need outside help.

Teachers are no different from the general population, and to expect them to be experts on financial products, the emotions behind spending money and all the rest is unreasonable.

There are two possible answers:

There are two possible answers:

- Train teachers and provide resources

- Commission experts to deliver workshops for students

Our research showed that these two models are not at odds with one another. Staff can be trained to deliver aspects of financial education, but also believe that students benefit from expert speakers – and in many cases prefer this option. When asked to reflect on the choices that face them currently, nine out of ten believe that “Pupils learn about personal finance better from speakers with specialist knowledge”.

At The Money Charity we would be very happy for teachers to be trained so that they were in a position to deliver the entirety of a good financial education. But in the current circumstances, any healthy provision of financial education must involve a mixture of outside expertise and additional work from school staff. The Money Charity calls on policymakers and school leaders to recognise this mixed method as the optimal model for delivery.

Improving the evidence for what works in financial education

Interestingly, teachers also say that further evidence for the value of financial education would improve its standing in their school. While it is not the key driv er of what a school chooses to focus its energy on, teachers we interviewed cited a lack of faith that it works. So, the evaluations of what works currently being undertaken by the Money Advice Service and its successor is crucial to the development of financial education.

er of what a school chooses to focus its energy on, teachers we interviewed cited a lack of faith that it works. So, the evaluations of what works currently being undertaken by the Money Advice Service and its successor is crucial to the development of financial education.

Our recommendations for policymakers

Create incentives to teach students about finances – This should include at least one of:

- Putting holistic financial education into the Maths curriculum

- Making financial education in PSHE part of Ofsted’s common inspection framework and examining PSHE.

Whether we like it or not, the priorities that school leaders transmit to teachers are driven by grades and inspections. The only way to ensure financial education is afforded the priority that teachers believe it warrants is to use these mechanisms.

‘State that schools must teach it but not need to examine it officially – if it was on an Ofsted CHECKLIST EVERY SCHOOL WOULD TEACH IT IMMEDIATELY {teacher’s emphasis]’

Provide funding for financial education – What is clear from our research is that teachers are simply not currently prepared to deliver good financial education. Both through teaching resources and direct delivery from outside experts this can improve, but will need funding.

Our recommendations for Schools

Create ownership and leadership for financial education – Our conversations with teachers showed that one of the key impediments to good financial education is leadership.

Give financial education a home – It might not be obvious whether it ought to sit in Maths, Citizenship, PSHE or some mix of those, but teachers told us that the important thing is that the ownership is clear, whether the responsibility is held by a single department or shared.

“Maybe because financial education and maths link so well, maybe we should make part of the maths curriculum linked to real life and financial skills”

Get outside help – Two-thirds of teachers believe that staff in their schools don’t have the skills to teach financial education. This can only be solved with a mix of both training and delivery from outside experts.

“A mixture of both direct delivery and teacher-led classes is best”

* About the survey The Money Charity bases this piece on a survey of 126 teachers and in-depth interviews with a further six. A description of the methodology can be found in the PDF version.

Note: Where quotations are marked “XYZ”, they are taken from interviews. Where they are marked ‘XYZ’ they are copied and pasted from responses to open-ended questions in the survey.